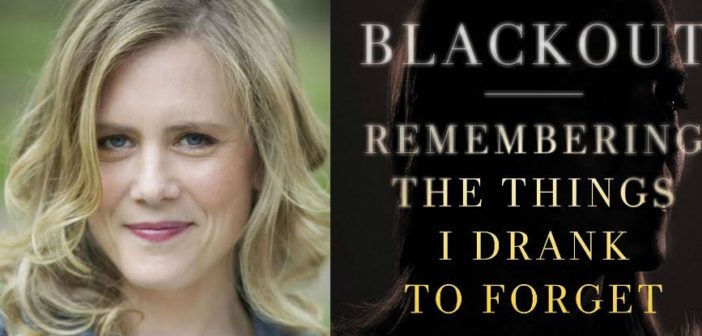

Sarah Hepola’s memoir, Blackout: Remembering The Things I Drank to Forget, has already garnered an astounding array of ink, from The New York Times to Jezebel to, um, us in the first part of this interview. In part two, the Dallas-based author discusses “futon alcoholics,” AA bashers and why a child-friendly version of her book would be three pages about her cat.

Sarah Hepola’s memoir, Blackout: Remembering The Things I Drank to Forget, has already garnered an astounding array of ink, from The New York Times to Jezebel to, um, us in the first part of this interview. In part two, the Dallas-based author discusses “futon alcoholics,” AA bashers and why a child-friendly version of her book would be three pages about her cat.

Anna: Was there any part of you that was concerned about the impact the book might have on your career or people’s perceptions of you?

Sarah: Yes, but probably not in the way you mean it. If the book was bad, if I was somehow exposed as a terrible long-form writer, that would have been hard for me. I was terrified to swing and miss. But I never thought the revelations about drinking would hurt my career as a writer, because a) my sins are fairly garden-variety, and b) I was already writing about my excessive drinking before I quit. I did worry about how the book would affect my family, and my friends, and I still worry. But so far, we’re good.

The problem I am currently having, however, is friends’ children. That one blindsided me. My friends have kids who are getting old enough to read my book, and so they’re curious. How do you explain: The nice lady who hangs out with Mom and Dad had some really dark times, and she wrote an entire book about it, but you can’t read it? Ugh. What is the right age to read Blackout? I don’t know the answer to that. I joke that I’m going to make a children-friendly version of Blackout, and it’s going to be three pages about my cat.

Anna: Since people who feel like drinking is not a choice but a necessity tend to ignore warnings, what do you think is the best way to get through to them?

Sarah: Stop laughing along when it’s not funny. Stop pretending it’s all okay. In my group of high-functioning binge drinkers, people are hugely motivated by public perception. If they start sensing that what they’re doing is uncool, or people have lost esteem for them, it will snap them to attention.

Then you have the private drinkers, the futon alcoholics, who probably got the message long ago that the way they drank wasn’t cool. That’s a harder one. I was like that, too, in my final years, and what caught my attention was how I saw my soul slowly dying. Mine was a realization that I may not die or wind up in jail, but my life would never change. My prison would be this same sad bullshit, for the rest of my life. That scared me, and being scared is a good thing. It leads to change.

Anna: Was mentioning 12-step in your book a decision you grappled with?

Sarah: Absolutely. I wrote three essays for Salon about quitting drinking, never mentioning AA, and over the years, I would get these emails that said: That’s so cool that you didn’t do the AA thing. I felt fraudulent, like a crucial part of my story was missing.

I’d had a terrible intellectual allergy to AA. I thought it was a bunch of lame slogans and Chicken Soup for the Soul-type clichés. I resisted it until I was too desperate to resist any more, and that program scooped me up and set me right again. That, by the way, is the oldest AA cliché there is: I hated AA, until it saved me.

Part of what helped wear down my resistance to AA over the years was discovering creative people who were in the program. Caroline Knapp wrote openly about AA in Drinking: A Love Story. Roger Ebert talked about AA. Marc Maron mentions it on his podcast. I found out David Foster Wallace had been an AA guy, though he was private about it, so it wasn’t made public till after he died. Infinite Jest is a masterwork about addiction and our endless, numbing access to pleasure, and it was inspired by his time in a halfway house, and so if AA can work for the best, smartest writer of his generation, then maybe I should shut up about the slogans for a little bit?

Those people opened the door for me. And if I was going to write an honest account of my drinking, and how I stopped, I couldn’t do that without talking about AA. Of course I could have said “a 12-step program,” or “a secret meeting,” but does anyone really think that’s a meaningful dodge? Maybe it is to some people. I don’t understand that.

I’ve taken a few hits for talking about AA, and I get it. I try to be careful not to sound like a spokesperson or an authority. I’m just a writer trying to make sense of her life on the page. But ultimately, the way I interpret the 11th tradition is that I will always protect your anonymity in the program, but there are times when it might make sense to reveal my own.

Anna: What are your feelings about some of the loud voices out there that criticize 12-step programs?

Sarah: Conflicted. Frustrated. On one hand, I’m sympathetic to the idea that 12-step programs have had a lock on recovery for a long time, and 75 years after AA started, we might be overdue for a reckoning about how to best treat addiction.

On the other hand, the critiques I’ve read betray a fundamental misunderstanding about how AA works. They often conflate rehabs—a for-profit industry that can charge thousands of dollars for treatment—with AA itself, which is a humble operation that asks for a dollar or two in donations. They often treat AA as far more strict and fundamental than I experience the program to be. You can find that, sure, but overall it’s a pretty elastic community, and they’ll bend to you. Literally, the only requirement for membership is a desire to stop drinking. That’s it. What’s funny is that writers act like they’re doing something shocking when they criticize AA—and given the traffic hits on those pieces, that may be true—but people bash AA in meetings all the time. Somebody will be like, “This program sucks, you guys are weirdos,” and it’s like: Cool, thanks for your share. It’s the most tolerant, patient group of people I’ve ever been around, so on that level, when people bash AA it feels a bit like aiming Uzis at a meeting of Quakers.

AA won’t fight back. Not at the organizational level, anyway. It’s a giant anarchy. It has no president. It has no spokespeople. It’s unprecedented in modern American life—a group of two million people with no political agenda, no causes whatsoever except to help the alcoholic who is suffering. So the people who grab all the megaphones are the ones who have beef with AA, and given the pervasiveness of the program, and the fact that it’s made up of human people with human flaws, there are so many people who have beef with AA. All I can do is speak from my own experience, which is to say it’s the only way I found to stop drinking. I also think it’s a powerful antidote to the soul sickness of American life.

I’ve thought about writing about these topics, but again: How much do I flout the anonymity clause? I feel like my hands are tied to defend someone I love and someone who saved me. It’s frustrating. But I also think this broader argument about how we treat addiction is important, because addiction affects so many lives. So much is at stake. I’m interested in this new movement to bring people in recovery together under one banner to make policy change, like the Unite to Face Addiction rally in October. That’s interesting to me. I need to learn more about it.

Anna: What have some of the people struggling with alcoholism who have contacted you said? Do you end up staying in touch with them and sort of helping them through the process of getting sober?

Sarah: Mostly people say: I know I need to quit, but I can’t. Sometimes they talk about why they’re resistant. They don’t want to be boring. Or they might have to leave their partner, who still drinks. Or they love booze too much and can’t live without it. And they know I felt that way, too—I was the person clutching the bottle to my chest with tears dripping down my face, and I was completely and utterly convinced I could not live a life without alcohol, but I did. So mostly they just say: Thanks for letting me know it’s possible. They usually don’t ask me to write back, and I couldn’t anyway, because it would overtake my life. But I read every note. Some of them are amazing: eloquent, tortured, insightful, funny. I think sometimes people just want to send a note into the void that contains the absolute truth about themselves. Afterward, you feel lighter. You feel a little bit closer to knowing who you are and what you want to do.

Sponsored DISCLAIMER: This is a paid advertisement for California Behavioral Health, LLC, a CA licensed substance abuse treatment provider and not a service provided by The Fix. Calls to this number are answered by CBH, free and without obligation to the consumer. No one who answers the call receives a fee based upon the consumer’s choice to enter treatment. For additional info on other treatment providers and options visit www.samhsa.gov.